DeepSeek mHC: Fixing the Hidden Chaos in Giant AIs

If you’re anything like me, you’ve probably spent the last few years glued to the whirlwind of AI advancements. From ChatGPT blowing our minds to models getting bigger and smarter by the day, it’s been a wild ride. But every now and then, something comes along that feels like a real paradigm shift – not just more parameters or fancier training data, but a fundamental rethink of how these beasts work under the hood. That’s exactly what DeepSeek’s latest innovation, mHC (short for Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections), feels like to me. I stumbled upon their paper right at the start of 2026, and man, it got me excited. It’s not just another incremental tweak; it’s a clever fix to a problem that’s been lurking in neural networks for over a decade.

What the Heck is DeepSeek and Why Should You Care About mHC?

First off, a quick intro to DeepSeek for those who might not be as deep in the AI weeds. DeepSeek is a Chinese AI lab that’s been punching way above its weight class. They’re the folks behind models like DeepSeek-V2 and DeepSeek-Coder, which have consistently outperformed bigger names from OpenAI or Google on certain benchmarks, often at a fraction of the cost. They’re all about efficiency and open-source vibes, which is refreshing in an industry that’s sometimes too secretive.

Now, mHC? It’s their fresh-out-of-the-oven framework, detailed in a paper released on December 31, 2025. The full name is Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections, and it’s basically a smarter way to handle the “connections” inside neural networks. If you’ve ever wondered why training massive models can be so unstable – like, why do gradients explode or vanish, causing the whole thing to crash? – mHC tackles that head-on. It’s built on top of something called Hyper-Connections (HC), which was a cool idea from ByteDance in 2025, but HC had some serious flaws. DeepSeek fixed them by adding mathematical “constraints” that keep things stable without sacrificing performance.

In simple terms, imagine a neural network as a massive highway system where data flows like traffic. Traditional setups have single lanes with occasional skips (that’s residual connections, a staple since ResNets in 2015). HC tried to add multiple lanes for better flow, but without traffic rules, it led to pile-ups and chaos. mHC adds guardrails – specifically, it forces the connections to follow a “manifold” (a fancy math term for a curved space with rules), ensuring smooth, predictable traffic. The result? Models that train faster, more stably, and perform better, with just a tiny bit more compute overhead (around 6-7%).

Why is this exciting? Because as AI models scale to trillions of parameters, stability becomes the bottleneck. mHC could be the key to unlocking even bigger, smarter AIs without needing insane hardware upgrades. It’s like finding a way to make your car engine more efficient instead of just slapping on a bigger gas tank.

A Layman’s Guide to Neural Network Connections: From Residuals to Hyper-Connections

Okay, let’s ease into the technical side with some analogies. If you’re new to this, think of a neural network as a stack of layers, each processing data a bit more. Data goes in at the bottom (input), gets transformed layer by layer, and pops out at the top (output, like a generated sentence).

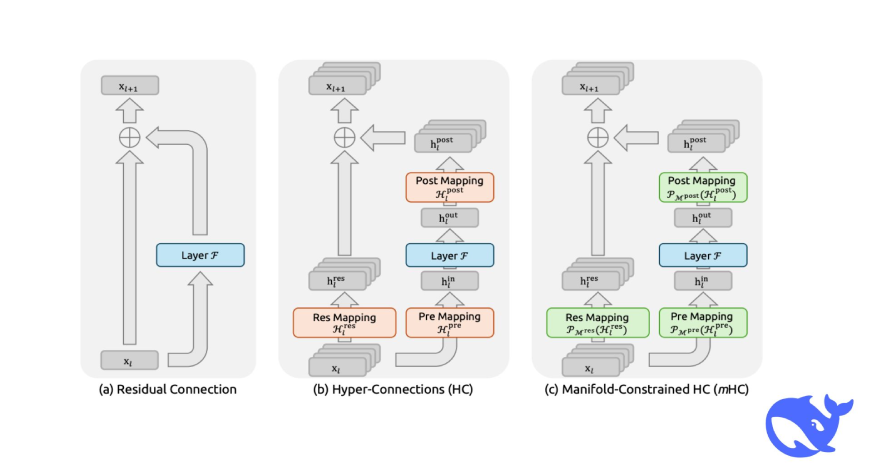

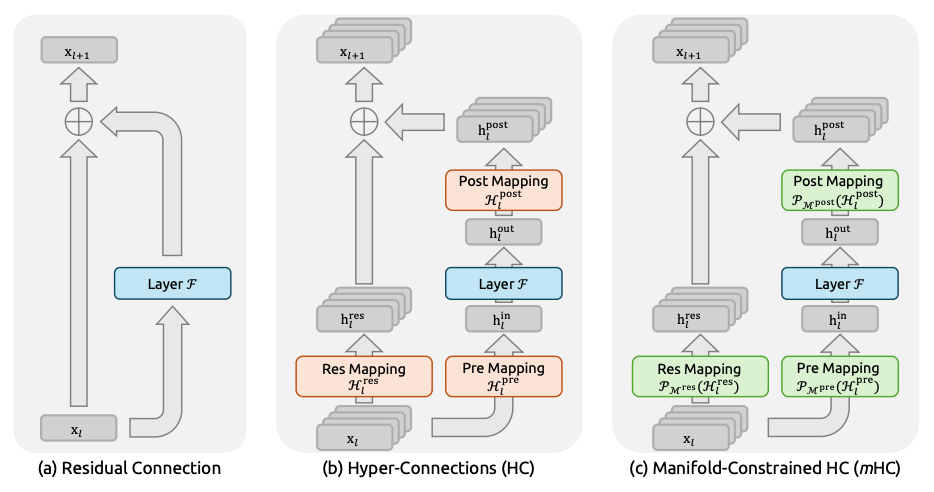

The big innovation back in 2015 was residual connections (from the ResNet paper). Without them, deep networks suffered from “vanishing gradients” – basically, as signals pass through many layers, they get weaker and weaker, like whispering a message in a long chain of people until it’s garbled. Residuals fix this by adding “skip connections”: the output of a layer is the input plus some transformation. Mathematically, it’s:

\[ x_{l+1} = x_l + F(x_l, W_l) \]

Here, \( x_l \) is the input to layer l, F is the transformation (like attention or feed-forward), and \( W_l \) are weights. The “+ \( x_l \)” is the skip, preserving the original signal. It’s like having a direct express lane alongside the twisty roads.

This “identity mapping” (where the skip is just the identity function) keeps things stable. But as models got huge, researchers realized single-lane skips might not be enough. Enter Hyper-Connections (HC), which expands the residual stream into multiple “streams” (say, n=4 times wider). Instead of one skip, you have matrices that mix and match signals across streams. It’s like turning that single express lane into a multi-lane interchange.

But here’s the catch: HC breaks the identity mapping. Those mixing matrices can amplify or dampen signals wildly, leading to instability. In experiments, signal gains could spike to 3000x – imagine traffic suddenly multiplying out of control! Training losses spike, gradients explode, and the model crashes. Plus, widening streams means more memory and compute overhead, making it impractical for giant models.

mHC steps in like a traffic engineer. It constrains those mixing matrices to a “manifold” – specifically, the Birkhoff polytope, which is a set of doubly stochastic matrices (non-negative, rows and columns sum to 1). Think of it as rules: traffic must balance out (no net gain/loss), stay positive, and mix in a controlled way. To enforce this, they use the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm, a iterative method to project unruly matrices back onto this manifold.

In everyday terms, it’s like adding speed limits and lane-balancing tech to prevent jams. The result? Stability restored, with signals amplifying by at most 1.6x instead of 3000x. And it only adds about 6.7% to training time thanks to clever optimizations like kernel fusion (merging operations into one efficient GPU kernel).

Source: Internet

Source: Internet

This diagram shows the core architecture of mHC compared to standard residuals and plain HC. You can see how mHC adds the manifold projection step to keep things in check.

Diving Deeper: The Math Behind mHC

In HC, the residual update becomes:

Norm preservation: Spectral norm ≤1, preventing amplification.

Closure: Products stay on the manifold.

Mixing: Like soft permutations.

The projection uses Sinkhorn-Knopp:

They also optimize infrastructure:

- Fuse RMSNorm, projections, and sigmoids into one kernel using TileLang.

- Use activation recomputation every \( L_r \approx \sqrt{\frac{nL}{n+2}} \) layers to save memory.

- In pipeline parallelism, overlap comms with compute.

This keeps overhead low – only 6.7% more FLOPs for n=4.

Check out this graph illustrating training stability. The blue line (mHC) stays smooth, while HC (red) spikes all over – clear visual proof of the fix.

The Proof is in the Data: Benchmarks and Experiments

Now, let’s talk numbers. DeepSeek tested mHC on models inspired by their DeepSeek-V3 architecture: 3B, 9B, and 27B parameters, all with Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) layers. They used n=4 expansion, trained on datasets proportional to size (e.g., 1T tokens for extended 3B runs).

Key metrics from the paper:

Stability: Loss gap reduced by 0.021 vs. baseline. Gradients stay steady.

Amax Gain Magnitude: HC hits 3000; mHC caps at ~1.6.

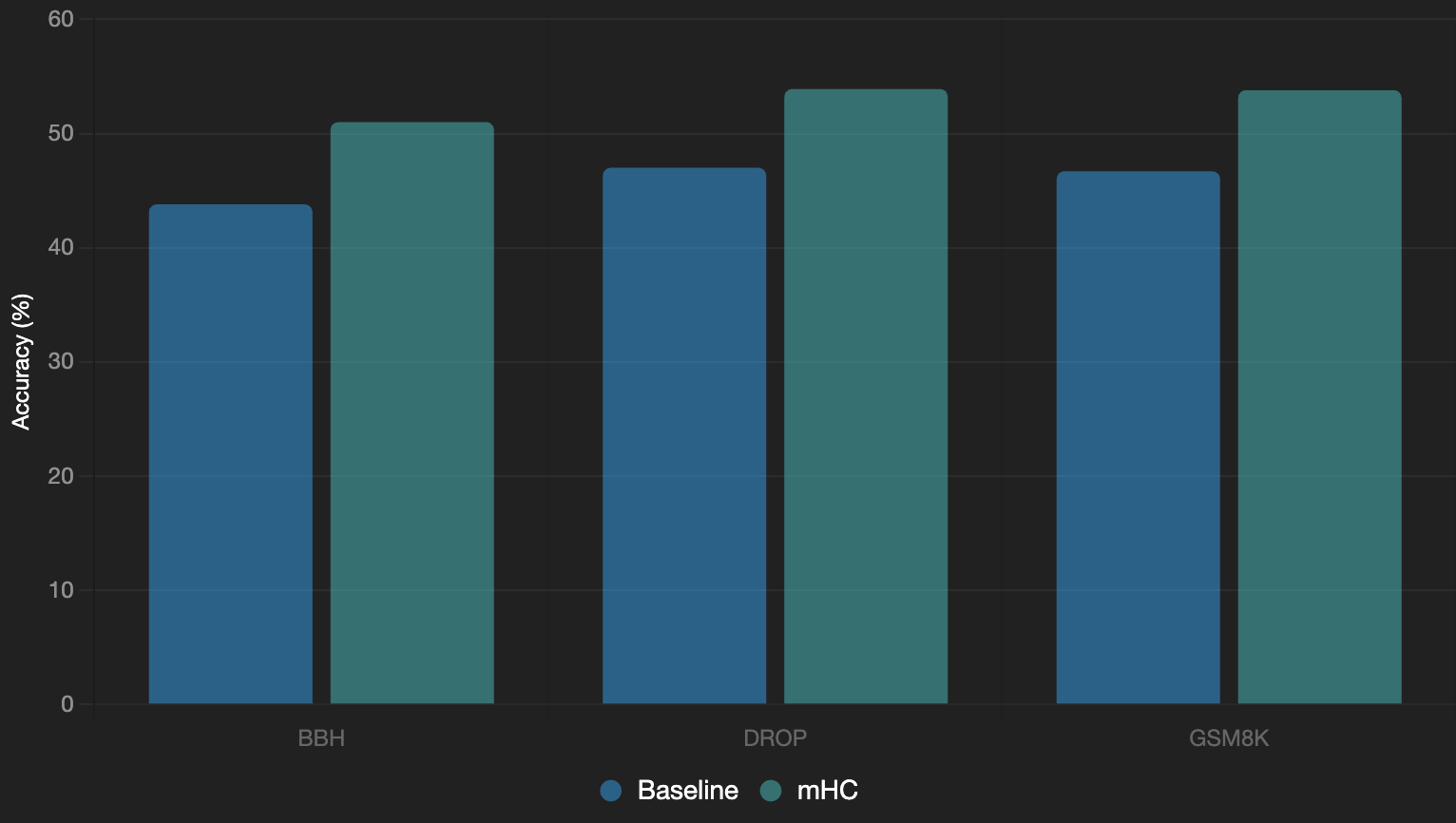

Performance: On zero-shot benchmarks for the 27B model:

| Benchmark | Baseline | HC (unstable) | mHC |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) | 43.8 | ~45–47 (est.) | 51.0 (+7.2) |

| DROP | 47.0 | Lower due to instability | 53.9 (+6.9) |

| GSM8K | 46.7 | Similar | 53.8 (+7.1) |

They also beat baselines on other tasks like TriviaQA and Natural Questions. Scaling experiments show the edge holds as compute increases from 3B to 27B, and with more tokens (Fig. 6).

In a Reddit deep dive, users noted mHC’s 2.1% lift on BBH overall, with stability improvements of three orders of magnitude.

To visualize, here’s a bar chart I whipped up based on the 27B results:

See how mHC consistently outperforms? That’s not just marginal; in AI terms, 7% jumps on reasoning tasks like GSM8K (math problems) are huge.

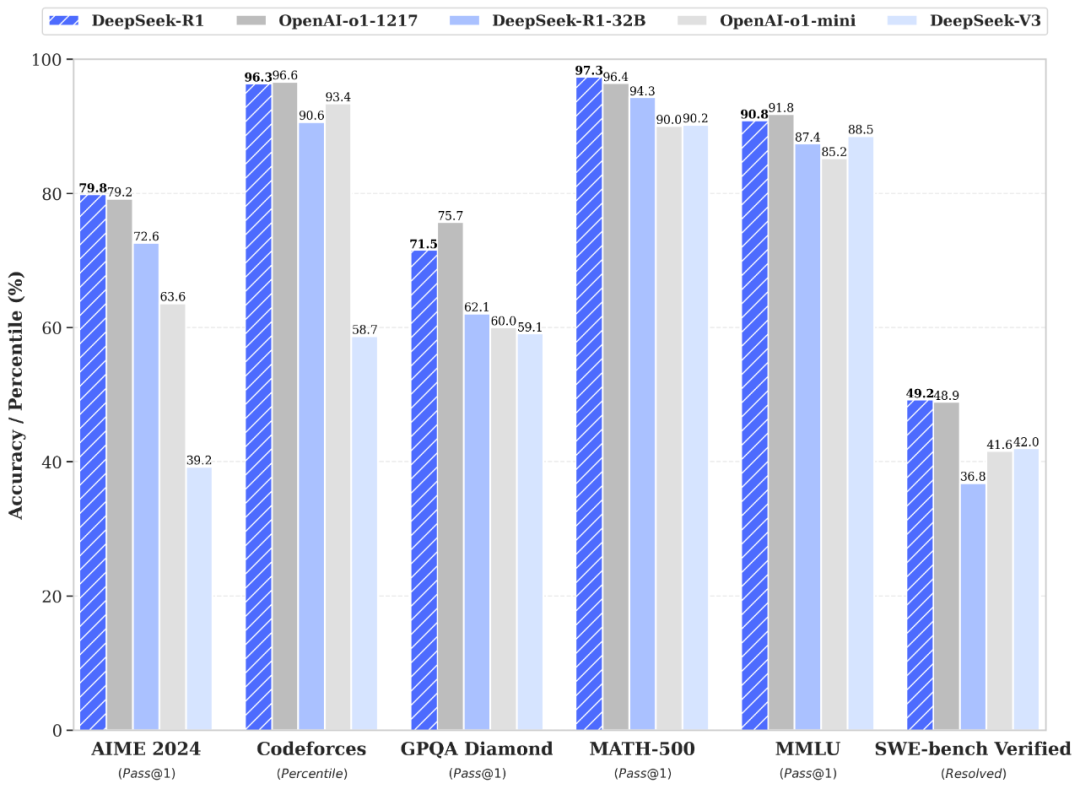

Another cool vis from sources:

Source: Internet

Source: Internet

This chart from DeepSeek’s R1 review (their likely mHC-powered model) shows broader benchmarks, reinforcing the gains.

Why mHC Feels Like a Breakthrough – And What It Means for AI’s Future

What I love about mHC is how it questions sacred cows. Residual connections have been untouchable since 2015, but DeepSeek shows they’re not optimal. By widening internal flows while keeping stability, mHC enables better “feature mixing” – the model can juggle more ideas per layer without losing track.

Implications? For one, cheaper training for big models. With only 6.7% overhead, labs like DeepSeek (or even hobbyists) can push boundaries without Meta-level budgets. It might accelerate open-source AI, as seen with their paper’s open release.

On the flip side, it highlights a split in AI: Big Tech chases agents and apps, while outfits like DeepSeek and Moonshot (with their Muon optimizer) tinker at the foundations. This self-doubt – “Is this really the best way?” – is how progress happens.

Potential downsides? The Sinkhorn iterations add compute, though optimized. And while tested up to 27B, trillion-param monsters might need tweaks. But early signs are promising; rumors say DeepSeek’s next flagship (maybe R1) incorporates it.

In layman speak, mHC is like upgrading from a single-core CPU to multi-core, but with software that prevents overheating. It could lead to AIs that reason better on complex tasks – think solving multi-step math or parsing dense docs – without exploding your electric bill.

Wrapping It Up: mHC as AI’s Next Big Leap

If there’s one takeaway, it’s that mHC isn’t just a patch; it’s a rethink that could scale AI further than we thought possible. DeepSeek’s work reminds me why I got into this field: the thrill of peeling back layers (pun intended) to find smarter ways forward.

If you’re inspired, check out the paper yourself or experiment with their models. Who knows? Maybe mHC will be in the next Grok update or something. Drop your thoughts in the comments – is this the breakthrough we’ve been waiting for, or just another hype cycle? Either way, I’m stoked for what’s next.